Economist Kenneth Boulding once said that “anyone who believes that exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.” Despite this warning, the mantra that “growth is good” remains barely questioned today.

Christopher Jones’ book The Invention of Infinite Growth provides an insightful review of how delivering economic growth has become the most powerful imperative in politics over the past seventy-five years despite growing evidence that it is also the greatest single threat to human sustainability.

Jones reminds us that the discipline of economics did not even exist in the 18th Century. Rather there was “moral and natural philosophy”. Of the early philosophers it was Malthus in 1798 who warned that population growth would exceed food supply. Adam Smith in his 1776 Wealth of Nations formulated the idea of the invisible hand of the market guiding even selfish interests into social benefit. However even Smith recognized that “Land constitutes by far the greatest…wealth of every extensive nation”.

David Ricardo in his 1817 textbook argued that landowners were poised to absorb an increasing share of wealth over time because the amount of land was finite and subject to the law of diminishing returns. John Stuart Mill published his Principles of Political Economy in 1848 in which he made the case that a stationary state was inevitable but a good life would still be possible. Nowadays the ideas of Smith and his peers are known as ‘classical economics’.

Later in the 19th Century, the works of Jevons and others were synthesised by Marshall in his 1890 economics textbook which many consider to be the birth of ‘neoclassical economics’. This coincided with the pivot from the term “political economy” to “economics” and the introduction of mathematical concepts into the field.

While the classical thinkers studied three factors of production – Capital, Labor and Land – neoclassical thinkers in the 20th Century dropped Land as an independent category subsuming it within Capital.

By the turn into the 20th Century the concept of economics as a discipline started to take hold, originating in the USA. With the USA blessed with abundant resources perhaps it was understandable that limitations on land or resources did not factor into economic thinking.

In the ‘new’ discipline of economics, there was no great emphasis on the desirability of “economic growth”. In fact the experience of the Great Depression brought forward the idea that a stable and static economy that met people’s basic needs was a desirable state of affairs. And after the Second World War there were great fears that the sudden removal of defence spending in the USA would lead to depressed conditions.

Instead the USA went through a post-war boom with wealth being shared widely in society and a substantial middle class created. With this experience, the idea that “growth is good” arose in the 1950s. Around this time the development of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a single indicator of economic heath became ingrained in economic and political thinking. Jones covers the historical development of this key indicator in some detail.

American economists Paul Samuelson in the 1950s and his student Robert Solow from the 1960s were influential in developing mathematical models of economic growth and promoting the desirability of growth.

With land captured within “Capital” and an implicit assumption that there would be no constraints or limits from the planet’s resources, the idea of earthly constraints was ignored. The prevailing idea was that market price signals would generate technological advancement and improved access to any required resources, or substitutes would be found. What’s more they could point to examples where this occurred.

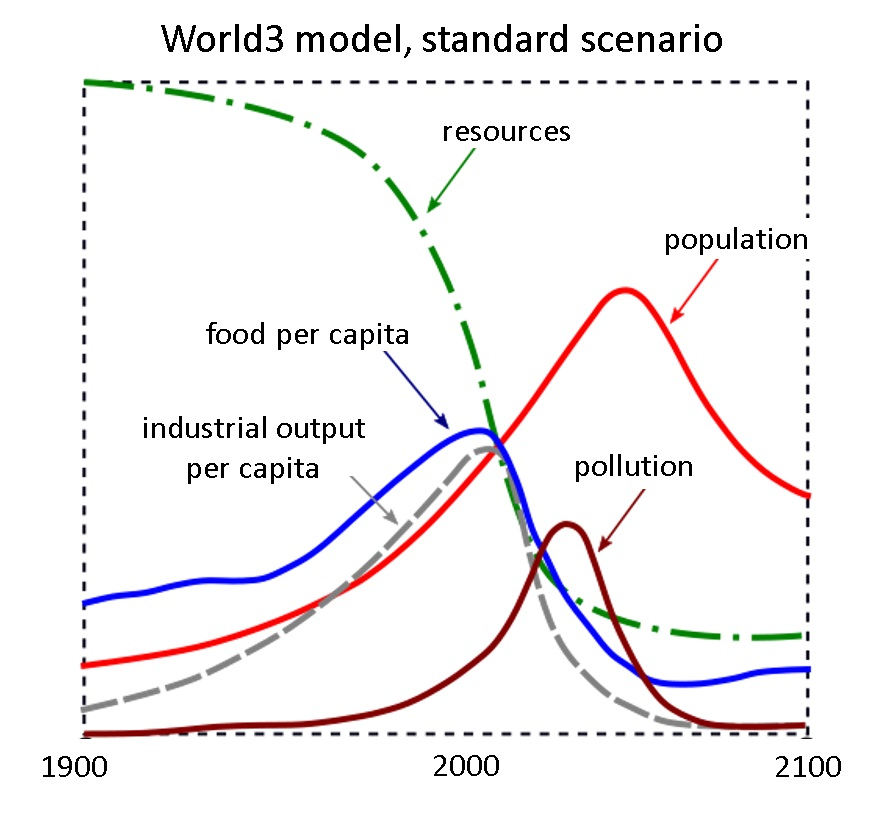

The “growth is good” bus seemed unstoppable. But when Limits of Growth was published by the Club of Rome in 1972, it garnered worldwide media attention. Here was an MIT team using newfangled computer modelling to demonstrate that negative feedback loops undermined natural systems necessary for human survival. A continuation of current exponential trends, they said, would end in a collapse scenario.

The report was condemned by the world’s most influential economists. Solow considered it was “worthless as science and as a guide to public policy”. The Limits of Growth report, and a small cohort of economists warning of the constraints of the natural world, turned out to be barely a speed bump on the road to economic growth.

The “growth is good” view therefore pervaded economic thinking and influenced the new generation of economists mentored by Samuelson and others.

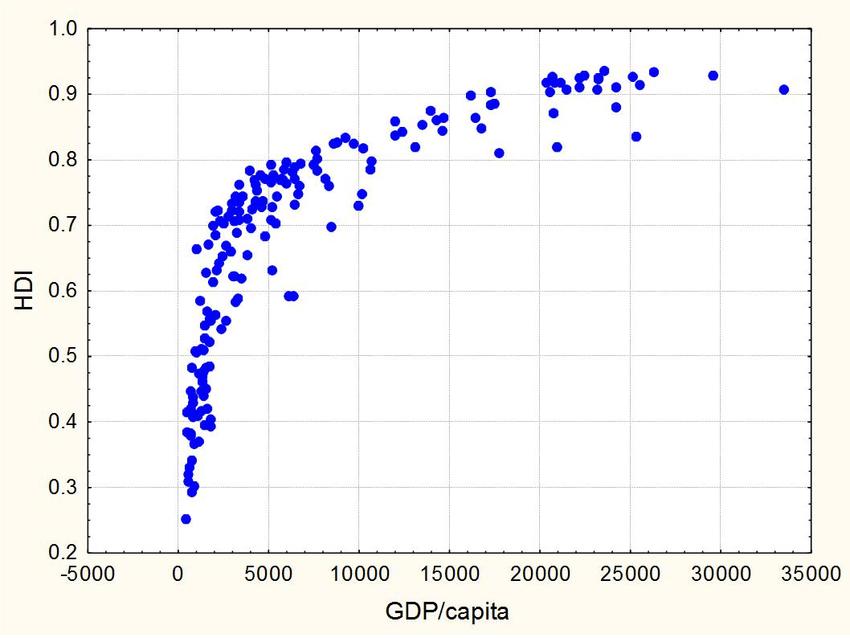

Fast forward to today. There is a greater recognition of the constraints posed by the natural world. More economists are questioning neoclassical theory. Some of these economists such as Herman Daly are profiled in the book. There is also more questioning of the marginal benefits of increasing wealth on well-being, as demonstrated in the accompanying chart.

Nevertheless, the most influential economists of today remain the neo-classicists who continue to train the latest generation of economists. Author Christopher Jones has chosen to focus on economists instead of business executives and lobby groups because economists pioneered the idea of infinite growth and retain a privileged position to pronounce on its possibilities. They have provided the intellectual legitimacy for vested interests opposed to environmental sustainability.

The Invention of Infinite Growth achieves its goal to rethink growth in the context of the present realities of climate change, stagnant (or declining) well-being in developed countries, rampant inequality and a planet under duress. It is essential reading for understanding how our thinking has become paralysed and blinkered by lived memory. Christopher Jones has given us a well-researched, informative and timely wake up call.

The reviewer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

Main image credit: dmarr515 via Pixabay

For posts on similar themes, consider:

Does our Fate Rely on this Graph?

Every Time History Repeats, the Price Goes Up.