Why did Homo sapiens triumph over other Homo species? And then how did we become the dominant species on the planet? Academic Hanno Sauer addresses these questions and more in his insightful book “The Invention of Good and Evil: A World History of Morality.”

One reason for our success is that we, as a social animal, have a spontaneous and surprisingly flexible capacity for co-operation. Modern group experiments show that humans are intrinsically generous and altruistic but that an individual within a group has a better chance of “winning” if he is selfish, even at the expense of the group. Sauer argues that in our original small groups the benefits of co-operation could be policed by the bonds of close kinship, leading to co-operative and egalitarian groups of Homo sapiens who could protect each other from predators, hunt together, safeguard each other from hardships, and as a result become better at surviving.

As we grew in numbers the bonds of kinship became weaker. To enforce the benefits of co-operation, but in larger groups, we acquired the ability to monitor and punish the violation of norms. Our group-oriented moral psychology became punitive. Through countless generations, aggressive individuals who would not conform would be ostracised or even killed, thus allowing co-operative genes to dominate. In so doing we developed a powerful punitive instinct with an unfortunate tendency to excess, leading to a delight in cruel punishments.

With this development we acquired the ability to live together in larger groups enabling development of techniques for clothing, housing, weapons, food and knowledge that gave us an advantage as cultural learners. We could pass on knowledge from generation to generation. We became social learners. We learnt to trust and imitate others through shared values and identity markers.

The technological advances enabled by social learning allowed us to produce economic surpluses under the right conditions. This change is often taken to correspond with the birth of agriculture and the first civilizations around 5,000 to 10,000 years ago.

Despite our inherent preference for egalitarianism, societies of ever-increasing size emerged which could only be organised by imposing hierarchy and funding a central bureaucracy through taxation based on grain. Thus evolved a small ruling elite (with inherited privileges) and a majority of exploited, oppressed people. This is when slavery, foreign rule and inequality bloomed, creating the ideal breeding ground for religions based on salvation and afterlife.

In the last five hundred years, socio-cultural evolution progressed sufficiently that social norms and institutions emerged which began to question the function of kinship as a key organizing principle of society. The roots of such evolution in Western Europe at least can be traced back to changes in kin rules adopted by the Catholic Church some one thousand years ago. This evolution was accelerated by the growth of markets and the emergence of democracy.

Canadian psychologist Joseph Henrich coined the term WEIRD for the people who came to most represent this cohort – Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic. The WEIRD perspective has dominated western morality ever since. And counterintuitively, studies have shown that WEIRD people are comparatively less loyal to family and community, but more altruistic and cooperative towards strangers [presumably of their own race] than the global average.

Moving into the last century, horrific examples of war, genocide, discrimination and exploitation led to a call for greater equality. However this highlighted the tension between two ideals – individual freedom and equality – and it seems almost impossible to achieve both at the same time.

In the final chapters of his book, Sauer discusses some the hot issues of the current moral climate.

He describes the “woke” movement as an understandable reaction to the slow progress toward equality and removal of social injustices. The frustration from not being able to achieve fair conditions straight away has instead led to linguistic changes, for example use of pronouns, which are easier and faster to achieve. He predicts that wokeness will remain but in a weaker, tamer form and become endemic. The process, already in progress, will involve wokeness being watered down and absorbed by capitalism and meritocracy where it will survive but be stripped of its most radical manifestations. The West’s downfall from “woke” will fail to materialise.

He also discusses “fake news”. He points out that since we became social learners we have been reliant on second-order evidence – information provided by people we trust rather than on direct evidence. The modern problem is that our affiliations have become more politically polarised.

But, he argues, our political beliefs are superficial, unstable and uninformed; polarisation is largely an emotional phenomenon; we distrust other people if we cannot identify with them; we begin to hate them if they do not belong to ‘us’.

However, in reality there are more things that we share with each other than divide us. The moral values that unite us run deeper than we believe, and the political divides that separate us run less deep than we think.

The Invention of Good and Evil is a fascinating look at the history of humanity, not just morality. It offers plenty of insights into the human condition. And in itself provides a welcome antidote to the tsunami of disinformation.

The writer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

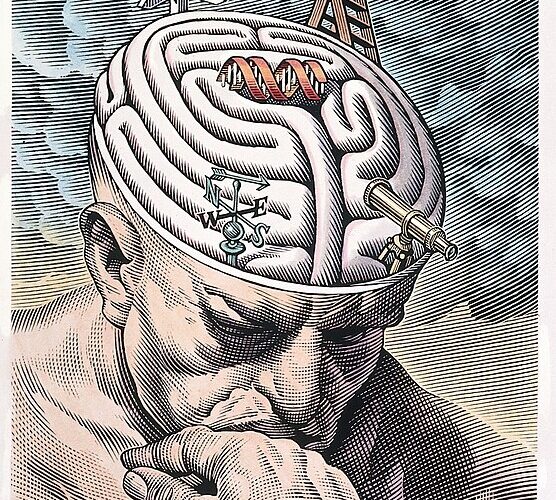

Main image credit: Bill Sanderson

For posts on similar themes, consider: