Henry Lien’s book Spring Summer Asteroid Bird provides an introduction to a common form of Asian storytelling known in the West by its Japanese name kishotenketsu.

To understand and appreciate kishotenketsu we need to quickly recap the traditional three-act story structure. In this familiar structure the first act sets up the story and introduces the catalyst that propels the protagonist on their ‘hero’s journey’. By the end of the first act, we have met the main characters and understand the protagonist’s mission. In the second act, multiple obstacles are encountered by the protagonist from antagonist forces. Often it appears the protagonist will achieve his goal at around the half way mark only for his plans to collapse and by the end of the second act the antagonist looks victorious. In the third act, the protagonist gains some inspiration and rallies to defeat the antagonist (or fails if it’s a tragedy) in the climax thus providing resolution to the story.

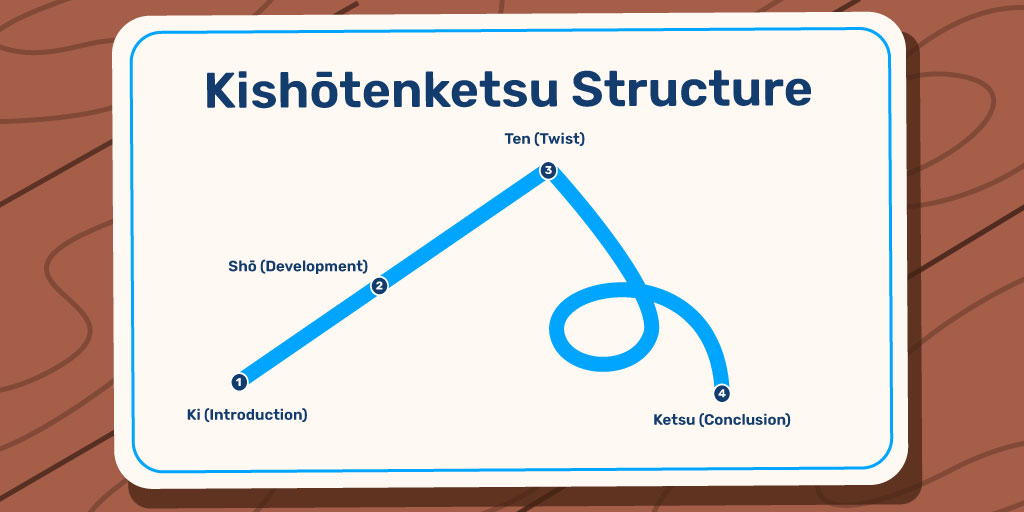

Henry Lien describes how kishotenketsu is a four-act structure. It is not symmetrical. The first act introduces the character and setting. In the second act the story develops through a series of events. The third act features a surprise twist or introduction of a brand new element which challenges the assumptions in the first two acts. The fourth act harmonizes the preceding elements and sometimes concludes abruptly leaving the reader/viewer to draw their own conclusions. The story arc when shown graphically depicts how disruptive the third act twist can be.

The third act new element is quite different to traditional approaches where most of what’s needed to conclude the story has already been introduced. Another feature that’s different is that the story often lacks the conflict and tension in the first two acts that is common in three-act structures.

Lien illustrates kishotenketsu by examining well-known stories using the form including Academy Award winners Parasite and Everything Everywhere All At Once. By doing so he demonstrates that western audiences can readily embrace the four-act structure. However he also shows how the original story of Mulan and other Eastern stories can be lost when translated into traditional three-act forms.

Most of the book covers case studies of four-act storytelling. This includes nested and circular structures. He even uses video game stories to illustrate the form. Indeed, kishotenketsu is common in manga and anime stories.

The most interesting chapter is on the values dictating the four-act structure. The third act twist gives us the opportunity to see how a character responds to an unplanned or unwelcome complication. With circular stories multiple passes at the same event reveal more than an individual linear account. Nested storytelling allows deep relational networks to emerge that transcend individual experiences.

Lien finishes by reviewing one of the most famous and complex nested stories – 1001 Nights.

Helpfully the book ends with questions for the reader/writer that allow those interested to further consolidate their understanding and thinking on the four-act structure.

Spring Summer Asteroid Bird Is a very useful antidote to the formulaic western storytelling that we are most familiar with or, as writers, are taught. It provides a different perspective on how to think about story. For that reason alone it is worth a read.

The writer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

Main image credit: Hulu via campfirewriting.com

For posts on similar themes, consider:

Career Lessons from Writing a Novel