Rome was sacked by Gaul invaders in 390 BC, and in the 210s BC the Carthaginian general Hannibal wreaked havoc on the Italian Peninsula. Yet the Roman Empire survived and flourished over subsequent centuries, only falling to raiding ’barbarians’ more than five hundred years later.

Why did the early setbacks not lead to the fall of Rome while the later ones, when the Empire was at its grandest, did? The answer comes down to “complexity” and “energy”.

“Complexity” refers to the degree of a society’s organisational structure and social ranking, bureaucracy, laws and enforcement, and extent of specialized professions. As a civilization grows it becomes more complex and rigid. “Energy” in the Roman era meant manpower (including slaves), beasts of burden, heat from burning of wood, and solar energy on their lands in the form of agricultural crops for food and fibre.

The Rome of BC was low on the complexity scale and had access to surplus ‘energy’, enabling it to recover and grow. With each capture of new territory, the empire grew and brought in a wealth of ‘energy’ in slaves, energy-embedded goods, and food production capacity. During its rapid expansionary phase the city of Rome itself grew to a population of around 1 million. As the empire expanded it became more complex in order to manage, control and protect its extended boundaries and larger populations.

At the end of its great expansions, during the reign of Emperor Trajan, the ‘energy’ required to capture and retain additional territory was not paid back by the gains. Indeed holding some of the existing territory was proving to be a net drain on the empire, a symptom of overreach. And so over time, the empire found itself needing more energy than it could access in order to sustain itself. Something had to give. Early signs of trouble appeared in the mid-200s AD, and accelerated in the late-300s.

The fact that the invading ‘barbarians’ of the 400s were frequently welcomed by the locals in the outlying regions, was a reflection on the local’s lack of real connection with the elites of Rome, and on their relief from the crushing tax and societal burdens imposed on them to prop up a waning empire. The ‘barbarians’ often proved to be more effective at protecting the local region than the stretched Romans were.

Slowly but surely the empire broke down into a simpler set of autonomous regions requiring less overall ‘energy’ and ‘complexity’ to maintain. These new, simpler societies could no longer ‘afford’ some specialised professions, leading to a ‘dark age’ in arts, literature and innovation.

For the highly urbanised centers the ‘collapse’ was particularly catastrophic when they lost access to the energy (food) they had come to rely on from far flung regions. During Rome’s ‘collapse’, its population dropped from around 800,000 in 400 AD to between 100,000 and 250,000 by 500 AD1.

The mechanism of break down or ‘collapse’ described above is that advanced by Professor Joseph Tainter in his outstanding book The Collapse of Complex Societies. Tainter convincingly identifies the reasons for the collapse of many highly-evolved past civilizations through the lens of the law of diminishing returns of ‘energy’ and complexity.

We can use Tainter’s framework to consider how the return on energy has applied in modern times. When high density energy was first harnessed in the form of coal to run steam engines, our access to new energy leapt. New machines could transport and produce goods at an ‘industrial’ scale and at cheaper cost, and allowed other technological advances.

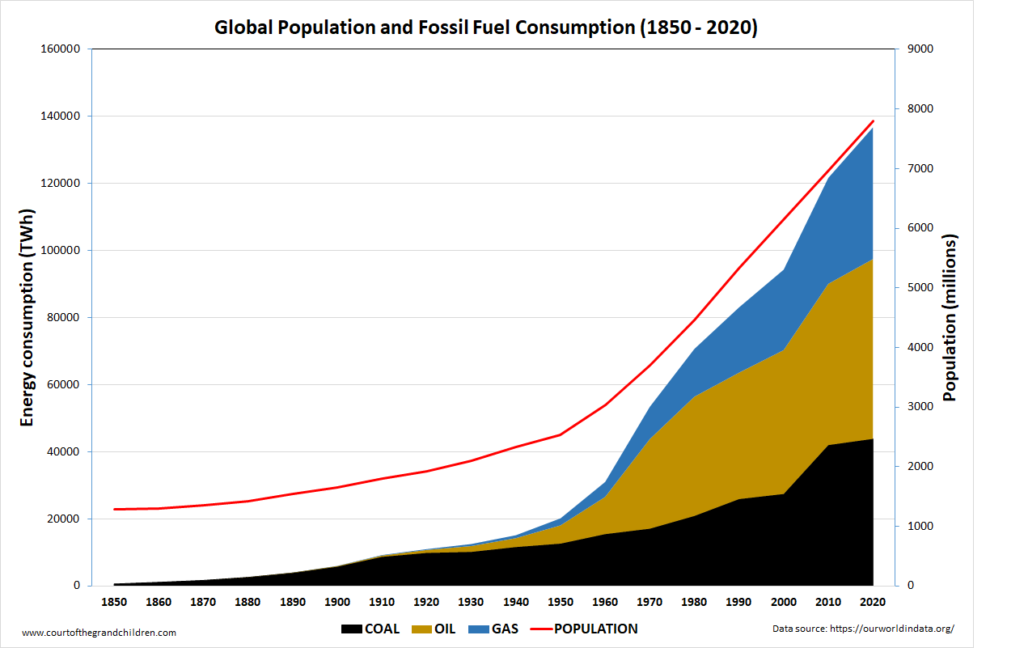

Then, when oil was harnessed in the 20th Century another massive source of cheap energy was unleashed. The consequences were breathtaking. Measured over the last seventy years, the population of the planet has tripled and the global GDP expanded thirteen-fold. Nearly 90% of all the fossil fuel ever burned has occurred in this period. That’s within a single lifetime.

At the current rate of consumption, we will have burned most of the remaining fossil fuel resources within another one lifetime. But well before we contemplate that outcome, the more immediate concern will be the climate-changing emissions into the atmosphere of heat-trapping carbon dioxide and methane.

To mitigate global warming requires the development of an alternative abundant source of energy to substitute for fossil fuels. The path being taken so far is with renewables such as solar and wind. By definition, a shift to renewable energy will involve an investment yielding a diminished ‘economic’ return. After all, it will duplicate existing efficient energy infrastructure, which is why there is so much resistance to a rapid transition so far. (And yes, we should be viewing this ‘investment’ in more holistic terms than just conventional economics)

To effectively make this transition will also require more complexity as new rules need to be put in place and all nations need to meaningfully participate in reducing emissions for a successful outcome.

When we look at the history of ancient empires, we see their successes corresponded to access to significant amounts of cheap energy, for example by capturing new territory with the resources that brought. The present day equivalent would be to develop even cheaper energy through significant cost reductions in solar, transmission or storage technologies, or breakthroughs in nuclear fusion technology. This focus on research and new technology is advocated by Bill Gates.

However, any such energy breakthrough on its own will not be sufficient. It would need to be accompanied by a paradigm shift in how we fit in our place on the planet. We have seen that energy boosts can lead to dramatic increases in population. Unfortunately, the planet is already over-exploited, with estimates that we currently consume natural resources 1.7 times faster than the earth can renew them.2

So we see that humans as a species have created a world which is highly complex and reliant on constant energy inputs. To manage the threat of global warming and over-exploitation of the planet will require substituting fossil fuels with renewable energy and, just as importantly, redefining what a sustainable economy is.

The grim alternative drawn from history is a ‘collapse’ in the global urbanized population over a short period of decades.

What can we do as individuals?

The first step is to talk openly and honestly about the dilemma we face. Consider the advice of climate communicator Dr Katharine Hayhoe who advocates starting conversations based on shared values like kids, community, or faith and why the issue matters to us. An important second part is to talk about hope and the solutions that are available.

Grant Ennis does us a favor by identifying the most effective thing we can do to achieve positive change. He shows that joining or starting a small community action group allied with other aligned groups and advocating for legislative change is the most effective means of achieving positive action, and why this approach can be more powerful that individual action.

But even if you can’t do these things, you can still do something. Don’t underestimate your contribution. For example, if you worry that your superpower is ‘only’ baking cakes, then bake cakes to support an individual or action group seeking positive change. Listen to Ayana Elizabeth Johnson’s TED talk to help you find what climate action would bring you joy.

Finally, Dr Bob Rich has some advice for people prone to environmental despair: “You can only do the best that you can do. Doing so can give your life meaning and purpose, making it worthwhile no matter what happens.”

In this 21st century, humanity has reached an apex in technological advancement. At the same time we have become the most invasive and destructive species on the very planet that has sustained us to date. Never before have so many people been alive and spread so widely on the planet. They all have a stake in the outcome, none more so than our children and grandchildren.

Our technological prowess shows we can solve the most challenging of technical problems. But to solve our climate and environmental dilemma we will need more than technical solutions. We will need to overtly recognize and value the critical role of our planet’s ‘natural capital’ and adapt accordingly.

Our forebears have been here before. We can learn from their mistakes, indeed we must as the stakes have never been higher.

We are past complaining that ‘they’ should do something. There are no ‘they’, just us. It’s incumbent on us to go out and do the best that we can do.

The writer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

Main image credit: Diana Butacu at Pixabay

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rome

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecological_footprint

One Reply to “Every time history repeats, the price goes up”

Comments are closed.