The final iconic scene in the 1960s film Planet of the Apes is one of the most memorable in cinema history. Astronaut Charlton Heston discovers that the planet he’s been marooned on is in fact Earth and he has stumbled on the remnants of his own failed civilization some millennia later. It’s a stunning if fantastical moment.

Or is it? We have stumbled on failed civilizations in the past, admittedly not via time travel.

The most famous example is that of Easter Island. By the time Europeans first encountered the island in 1722 they found a small native population and hundreds of monumental stone statues, called moai.

The history of Easter Island has been pieced together by archaeologists. It turns out the now treeless island was once forested with trees, shrubs and ferns. The original band of Polynesian settlers used the timber for shelter, heating and building sea-faring canoes. The plentiful resources of the island resulted in increased population and a sophistication of the culture, which allowed a class structure and specialized skills like stone carving to develop.

Apparently, the moai represented deified ancestors. It was believed that the dead provided everything that the living needed and the living, through offerings, provided the dead with a better place in the spirit world. But over time, 21 tree species and all land birds on the island were made extinct. The human population fell and the moai were unable to help. 4

Another example is the Maya civilization around Tikal, in current day Guatemala. It was one of the largest of the Classic period Maya cities. It was the capital of a powerful state in the Maya kingdom, a position it held for nearly a thousand years.

It is best known for its pyramid-shaped temples, which appeared in one of the scenes of the original Star Wars movie. The most elaborate of the temples were built from 700 AD to the mid-800s after which large building suddenly stopped. Tikal’s population likely peaked around this time, but by 950 Tikal was all but deserted. It is striking how quickly Tikal collapsed after its grandest achievements.

Archaeologists attribute the collapse of Tikal to overpopulation and agrarian failure. The rainforest claimed the ruins of Tikal for the next thousand years. The first planned visitors to the site came in 1848, requiring several days travel through the jungle on foot.

In my last post, Every time history repeats, the price goes up, I echoed the need for sustained investment in substituting fossil fuels with renewable energy to mitigate global warming. Compared to previous civilizations’ failed reliance on monuments and temples, our technology gods seem to have a better chance of achieving the necessary substitution of fossil fuels over time.

However, our technology gods will not solve our excessive rate of consumption of the rest of the planet’s ‘natural capital’ which includes soil, air, water and all living things. For that we need to look deep inside ourselves and question the faith we place in growth and our consumer-driven society.

An unchallenged assumption is that economic growth is a good thing. It is almost ingrained in our psyche. But we should take a closer look at this assumption. The most widely reported measure for growth is Gross Domestic Product (GDP). But this only measures expenditure on goods and services consumed. It does not measure the loss of natural capital in producing those goods (it assumes natural capital is free and infinitely replaceable) and it also measures the expenditure on treatment and management of waste as if that expenditure is a net contributor to growth.

It should be self-evident that we need to limit the use of resources to not exceed the capacity of the ecosystem to regenerate them and, in addition, absorb our wastes. But we are already exceeding the balance. We humans are now consuming natural resources at a rate 1.7 times faster than the planet can renew them.2

“the biosphere is finite, non-growing, closed (except for the constant input of solar energy), and constrained by the laws of thermodynamics. Any subsystem, such as the economy, must at some point cease growing and adapt itself to a dynamic equilibrium, something like a steady state.”

Herman Daly1

Continuous growth and failure to achieve an equilibrium will lead to severe over-exploitation of our natural resources that will then only be corrected by rapid depopulation of our planet, as witnessed in the collapse of past civilizations.

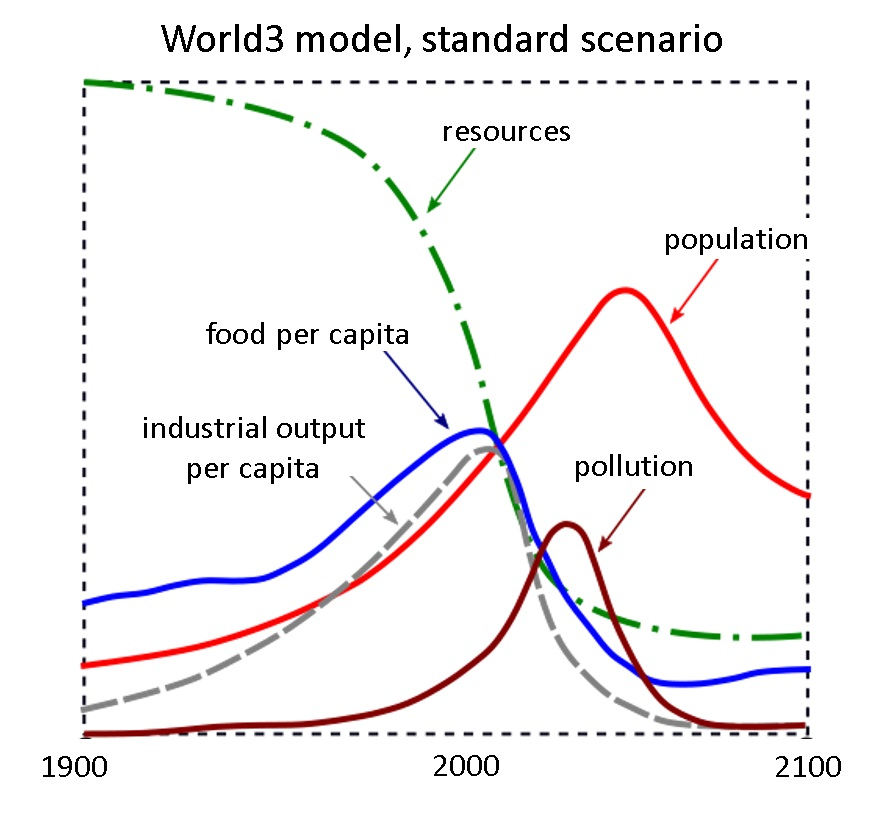

This understanding is not something new. The ‘standard’ business-as-usual scenario forecast from the famous 1972 MIT-authored report, The Limits to Growth3 is, sadly, still largely on track.

The only scenario that produced a ‘soft landing’ involved more efficient use of resources, reduced pollution, prioritizing services over material goods, more durable designs, sustainable agriculture and matching birth and death rates.

We seem to have hardly noticed that the population of the planet has tripled and we have burned nearly 90% of all the fossil fuel ever burned in the most recent period of just a single life time.

Thinkers like Nate Hagens, Herman Daly and Thomas Homer-Dixon advocate for a change in our worldview to enable a sustainable future. Tweeters like @ClimateDad77, @martinrev21 and @ClimateBen remind us daily on the Twitterverse of the changes required. And groups like The Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy and Council for the Human Future provide information and mechanisms for people to participate in the advocacy of these principles.

I encourage you to become more informed and be open to challenging our entrenched paradigm that ‘growth is good’. We don’t want future archaeologists to stumble upon vast abandoned swathes of dark-blue silicon panels draped across the country side, and ask what went wrong?

The writer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

Main image credit: 20th Century Fox

1 Herman E. Daly “Economics in a Full World” in Scientific American 293, 3, (September 2005)

2 Global Footprint Network per https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecological_footprint

3 Meadows, Donella H; Meadows, Dennis L; Randers, Jørgen; Behrens III, William W (1972). The Limits to Growth; A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books.

4 For a compelling alternative to this traditional narrative of the collapse on Easter Island, see my later post Fall of Civilizations