Between 1766 and 1805, the Dublin Society made grants for planting a total of 55 million trees in Ireland. This was on the back of at least seven parliamentary acts dating back to 1698 which envisaged planting and preserving trees and woods, by encouraging tenant farmers to plant trees and to register them in a county repository.

It was probably the first state afforestation scheme anywhere in the world.

The scheme was required because of the massive demand for timber for ship building, coopering and construction (a huge amount of Irish Oak was used for the rebuilding of London after the great fire of 1666). Together with wood for fuel, the remaining supply quickly shrank. The situation became so dire that in the early 1700’s ironworks had to close due to the shortage of wood fuel.

The 18th century Irish tree planting programs were ultimately unsuccessful and by the late 19th century Ireland’s forest cover had been reduced to a low of around 1%. It has since grown to around 11% today.

Ireland’s experience in deforestation is not unique. Over the same time period Scotland’s forest cover dropped to 4% and has since improved to 17%, while the figures for France are a low of 13% recovering to 31%

These latter figures are sourced from the article “Forests and Deforestation”1 which provides a more global perspective and which informs the rest of this post.

To start, let’s review at a high level the two reasons that forests are cut down:

- For the resources that they provide – the wood for fuel, building materials, or paper;

- For the use of the land – farmland to grow crops; pasture to raise livestock; or land to build roads and cities.

At a national level, demand for both of these initially increases as populations grow. There is more demand for fuel wood to cook, more houses to live in, and importantly, more food to eat.

But, as countries get ‘richer’ this demand slows. The rate of population growth tends to slow down. Instead of using wood for fuel there is typically a switch to fossil fuels, or more recently, to renewables. Crop yields also improve and so less land is needed for agriculture.

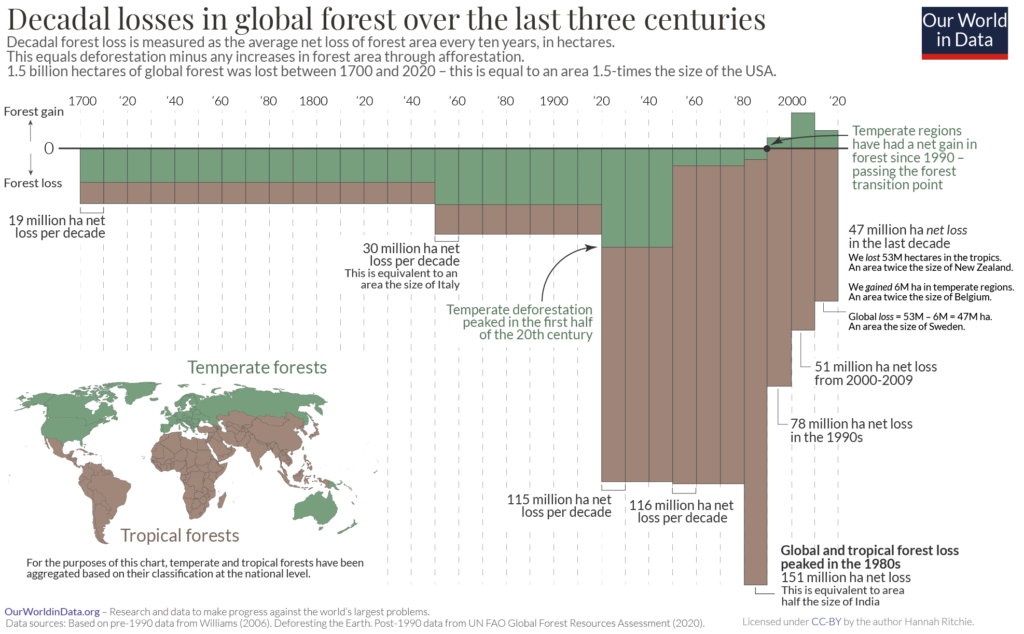

This trend can be seen at scale in the following graphic. It shows that the majority of deforestation over the last century has been of tropical forest, with the temperate forests of mostly developed countries making some recovery after centuries of depletion.

Compared to even a century ago, we have a better understanding of the impact of deforestation. Forests used to be largely valued only for their economic potential. Today we recognise the significant environmental values that forests provide. They support biodiversity, hold topsoil together, maintain water quality, are significant carbon sinks, and can provide inspiration for the soul.

And so the rate of destruction of rainforests has diminished over the last few decades, but it still amounts to an area the size of Portugal every year, against a diminishing stock of remaining forest.

As can be seen in the graphic, the vast majority, 95%, of global deforestation occurs in the tropics. Brazil and Indonesia alone account for almost half.

Although one might be tempted to put the responsibility for ending deforestation solely on tropical countries, supply chains are international, so this demand for resources and land is not always driven by domestic markets, but also by consumers in rich countries.

So what are the end products of this deforestation? A whopping 60% of tropical deforestation is driven by the production of just three agricultural products: beef, soybean (most of which is used as livestock feed2) and palm oil.

One of my earlier posts, Disrupting the Cow, looked at the potential benefits of replacing beef and dairy with more sustainable options. Since most tropical deforestation is driven by agriculture, the biggest impact we can make as consumers is to alter our diet preferences, especially reducing traditional meat and dairy intake.

There are many reforestation and tree planting programs in place worldwide. No doubt these are having an impact, but if we are not to fall into the same trap as the Irish in the 19th Century, there are more fundamental shifts in our consumer behaviour that can have as great if not more sustainable benefit for our environment.

The writer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

Image by Gennaro Leonardi from Pixabay

1. Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2021) – “Forests and Deforestation”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/forests-and-deforestation‘

2. https://ourworldindata.org/soy