Most older people today are unaware that in their lifetimes the population of the planet has tripled and we have burned nearly 90% of all the fossil fuel ever consumed. Did the population boom cause the explosion in fossil fuel use or the other way around? Author Vaclav Smil gives some clues to the answer in his meticulously researched book Energy and Civilization: A History.

Using first principles Smil compares the energy available from manpower to horsepower, through to water power, steam power and nuclear power. In doing so he identifies the big leaps forward in power availability to humanity. He identifies that each energy breakthrough, especially in the last five hundred years or so, took several generations to optimise and proliferate. He believes the same will likely be true for current trends in renewable power sources such as wind and solar.

Starting in pre-historic times, a crucial feature of human evolution that gave us tremendous physical advantages was bipedalism. Being able to walk on two legs freed the hands and arms for other purposes including fighting, tool use, and manufacture. The other prehistoric energy breakthough was the mastery of fire. This allowed for heating, cooking (making more foods digestible), and manipulating the landscape – and later for metallurgy.

Food was required to ‘fuel’ humans. The most energy dense of foods are the grains, with corn leading the pack. Starchy root plants were next best, then vegetables. Meat was rarer in diets but provided important fats and energy content.

Energy efficiency gains were achieved via mechanical advantage such as the wheel, levers and simple wedges. The first scaled improvement in energy availability was the use of animal power, typically oxen or horses. It is noteworthy that no native domesticable animal power was available on the Australian continent or the Americas. Therefore the pre-Columbian American civilizations depended solely on human (often slave) labour. However, the use of animal power came with a need to “fuel’ them. Horses were most demanding with up to 25% of food grown needed to feed the animate power.

Progress beyond animal power was slow. As long as animate labor remained the main prime mover of agricultural field work, the human population involved in agricultural work remained very high – more than 80%.

Even after the widespread use of water power for milling, animals and humans still dominated work up to 1800. For land transport horse-drawn technology was the best available at the time.

Wood was a staple fuel for heating, lighting and later for manufacturing processes particularly iron. The growth in the production of iron required increasing amounts of wood to produce charcoal. This lead to rapid depletion of forests for iron-making and shipbuilding in Britain during the 17th Century.

This fuel dilemma was solved with coal’s increasing use. The development of the steam engine, initially used to pump water out of coal mines, transformed thermal energy into mechanical energy and ushered in a transformative era of industrial growth.

Nevertheless wood was still the most important fuel world-wide before 1900 and coal dominated the 20th Century. The western experience belies the fact that the world now consumes more fuelwood and charcoal than ever due to the rapid growth of rural populations in low income countries.

The 20th Century saw rapid growth in oil over coal. Oil and its refined products had the advantage of being more energy dense as well cleaner and easier to transport and use. As a result, oil products transformed mobility and transport.

Agricultural mechanization led to greater availability of arable lands and greater productivity when combined with the use of energy-intensive ammonia-based fertilizers. This led to lower human labor requirements and the growth in urban centers. By 2015 nearly 550 urban agglomerations surpassed one million inhabitants compared to thirteen in 1900.

Another critical energy innovation in the late 19th Century was electricity, which has proven to be the most useful transformation of thermal and solar energy. The time from its invention to its first application in lighting and then widespread urban use was rapid. Now, modern societies could not operate without electricity.

The 1950s brought hope that nuclear power could be harnessed to provide almost limitless, low-cost power. That dream was undermined when a less-than-ideal technology was adopted for nuclear power generation, and subsequent accidents and concerns over long-term nuclear waste management resulted in escalating costs.

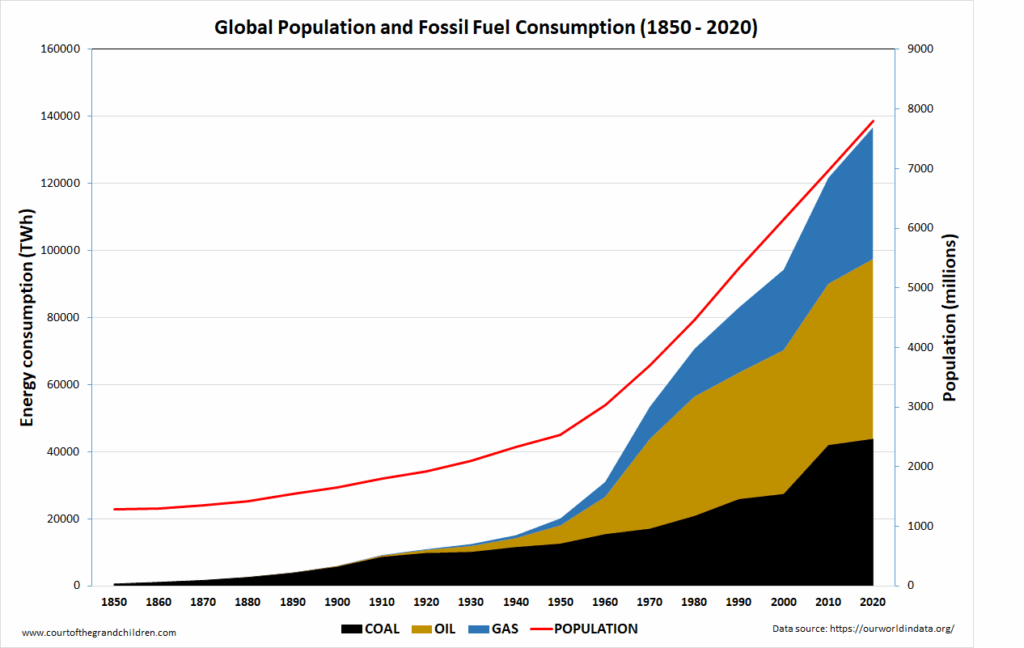

The massive growth in energy consumption over the last seventy years is illustrated in the following graph. It shows the coincidence of population growth with fossil fuel use. It also shows that despite the growth of oil and gas, coal consumption continues to grow.

The increased availability of energy has improved human wellbeing as measured by the Human Development Index. The accompanying graph shows the levelling off of wellbeing once per capita energy consumption reaches about 120GJ/capita.

In affluent countries the energy used to provide the physical necessities of life (food, shelter) has become a steadily smaller part of rising energy consumption. The production of a great variety of goods, provision of services, and transportation and leisure activities now consume the bulk of fuels and electricity in those countries.

Of course this begs the question of what will come of energy demand as low-income nations strive to improve their development and status. As an example, China’s per capita energy consumption increased five-fold between 1980 and 2015 as its economy modernised.

Smil notes that despite the apparent benefits of increased energy consumption, there is a significant price being paid beyond simply dollars. “The use of fossil fuels and electricity are the largest causes of anthropogenic pollution of the atmosphere and greenhouse gas emissions, and the leading contributors to water pollution and land use changes.”

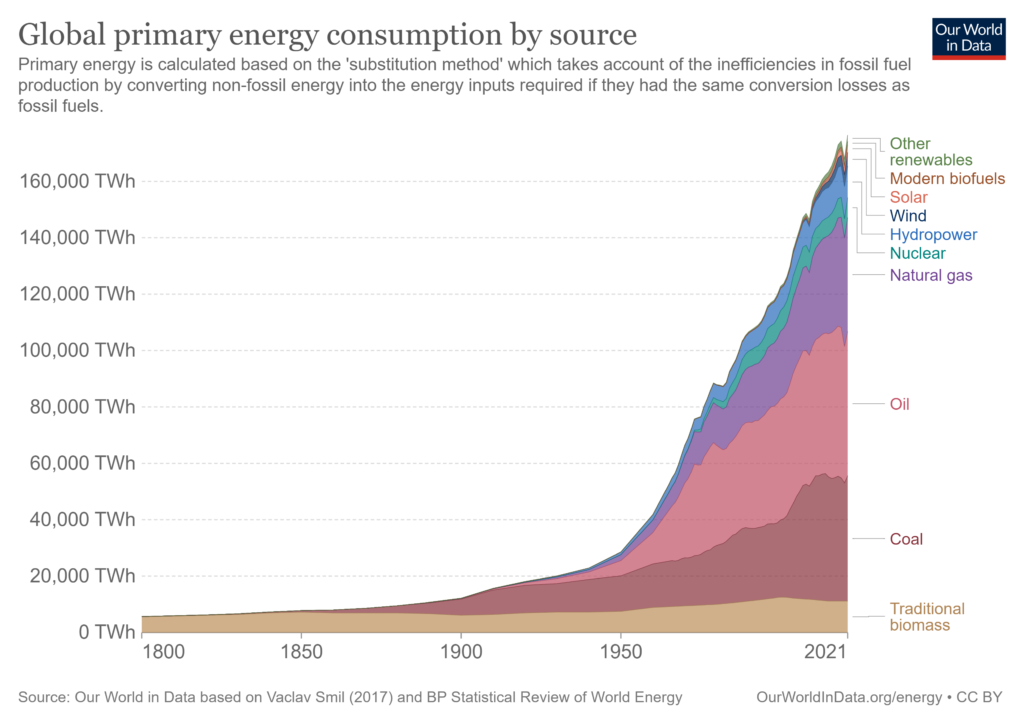

Smil contends that the substitution of fossil fuels with non-carbon sources may be several generations in the making given historical precedents, the dominance of fossil fuel in the global energy system, as shown in the chart, and the enormous future energy requirements of low-income societies.

Smil warns that “the multitude of changes attributable to global warming range from new precipitation patterns, coastal flooding, and shifts in ecosystem boundaries to the spread of warm-climate, vector-borne diseases.”

He believes that “there is no easy technical fix for anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. The only potentially successful approach to deal with these changes is through unprecedented international cooperation.”

He concludes that “the only certainty is that the chances of succeeding in the unprecedented quest to create a new energy system compatible with the long-term survival of high-energy civilization remain uncertain.”

The writer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

Main image credit: Hans via Pixabay

For posts on similar themes, consider:

The Race to 100% Renewable Electricity