How Australians voted at their federal election on 21st May 2022, made headlines across the country and internationally.

On election night as the votes were counted, shockwaves rippled across the country. In around ten percent of electorates, the voters had shunned the major parties and elected independent or minor party candidates running on strong climate platforms. They defeated well-known major-party representatives. As a result, this new loose bloc of climate-oriented candidates will now hold the balance of power in the new parliament. Further, the mainstream media who failed to press the major parties on their climate policies during the campaign, are retrospectively labelling the election as the ‘climate election’.

How did all this happen? Let me share my personal experience as a case study.

I live in the federal electorate of Kooyong, which takes in the leafy inner suburbs of eastern Melbourne. The electorate has been held continuously by conservative parties for more than one hundred and twenty years. For the last twelve years the sitting member was Josh Frydenberg, the high-profile deputy leader of the ruling Liberal (conservative) party and Australia’s Treasurer (equivalent to the US Treasury Secretary).

Back in the 2019 election, which was dubbed the ‘climate election’ during the campaign because of the stark differences between the two major party policies, the conservatives pulled off a surprise ‘miracle’ win. It seemed that ‘climate’ had cost the opposition Labor Party the election, and sunk the hopes of climate activists. In Kooyong, a high-profile Greens candidate, a climate-focused independent candidate and the Labor candidate had challenged Frydenberg. Although there was a swing away from him, Frydenberg still won comfortably by a 6% margin.

In the fallout of the 2019 result, a small group of locals in Kooyong formed what became known as the ‘Voices of Kooyong’ group. They were dissatisfied with the Frydenberg government’s lack of action on climate and other issues. So they followed the playbook of Cathy McGowan, whose local campaign a decade earlier had unseated an often-absent local member in a regional electorate.

Relying on the traditional, two-sided political model will not generate enough change and will continue to leave large sections of Australian society feeling left out.

Cathy McGowan

The Voices group searched for a high quality candidate prepared to run as an independent in Kooyong. They found an exceptional one in Dr Monique Ryan. Ryan was the head of neurology at the prestigious Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne. She lives in Kooyong and was tired of her community’s key issues being ignored by her local member.

With seed and match funding coming from Climate200, a community crowd-funded initiative to support pro-climate, pro-integrity, and pro-gender equity candidates, Ryan launched her candidacy in December 2021, six months before the election.

As I watched this unfold I was reminded of the post I had written earlier that year: The best thing you can do to tackle global warming, in which I outlined the conclusions of author Grant Ennis. He argued that legislative change is the most powerful thing you can advocate for, and that other popular measures were not only ineffective but could be counter-productive. So what Monique Ryan was striving for was the best thing: to enact climate legislation backed by the science.

What loomed large for me now was a quote from another post I had written on How to Cope with Climate Anxiety.

…do your best, work in every way you can think of for a survivable future, and one worth surviving in, but don’t worry about outcome. We do the best we can do, and it is good enough

Dr Bob Rich

And so I watched as Ryan and her small team courageously started on their journey to do the best they could do.

It was my turn. I started with the easier things. I donated to the campaign. I put up a campaign sign in my front yard (there were five other signs within a hundred meters of mine by the day of the election). I letterboxed leaflets, delivered merchandise, wore the campaign T-shirt whenever I left the house, and handed out how-to-vote cards during polling.

At the first volunteer induction meeting, run by inclusive leaders Brent Hodgson and Rob Baillieu, I heard that the campaign’s superpower was going to be its door knocking campaign. I took a deep breath… and put my hand up for it. It was something I could do and it was the best thing I could do.

I was there at the modest opening weekend of door knocking, the week when the Australian door knocking record was broken, and at the final weekend as well.

In the end Ryan’s campaign door knocked over 55,000 houses. The door knocking confirmed that climate action was indeed the number one issue for the majority of the Kooyong community. The campaign attracted a volunteer army of more than 2000 and raised over $1million from more than 3000 community donors.

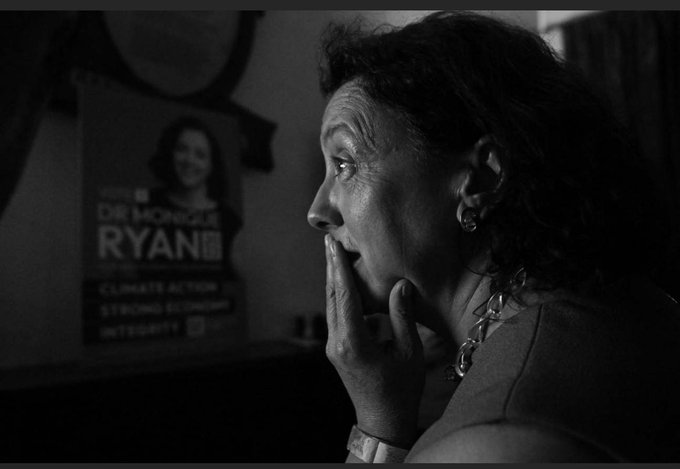

On election night I knew the campaign had done everything it could but I was unsure if it was enough to get past the Frydenberg juggernaut. Then the votes started to come in. As each polling station reported its numbers, Ryan’s numbers got better and better. Could our dream come true? By the end of the night all the election analysts had called the election in Ryan’s favour.

Similar stories played out in other electorates in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Perth and Canberra.

Australia had a new government. One that had to listen to our elected representatives and act on people’s wishes on climate action. I felt empowered as I’m sure all the other community-minded volunteers did right around the country. We had just demonstrated the truth behind Margaret Mead’s famous words: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

The writer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

Image credit (top): Twitter @theage_photo