Hydrogen is getting a lot of airplay as a means of decarbonizing the economy. There is talk of its use as a transport fuel, of replacing natural gas as a source of heat, of it being used to store the surplus output of solar and wind power stations, and of it replacing coke in steel production. If all this came to pass, it would usher in a ‘hydrogen economy’.

But first we should recognise that there is already a hydrogen economy. Seventy million tonnes of the stuff are produced every year. Hydrogen is used to produce ammonia as a feedstock for fertilizer manufacture and to convert heavy petroleum fractions into lighter fuel sources. Hydrogen is mainly produced on site with the primary method of production utilising fossil fuels. This process produces CO2 emissions and is often referred to as gray hydrogen.

But it’s the other ‘colours’ of hydrogen that are drawing most attention, namely blue and green hydrogen. Blue hydrogen is like gray hydrogen except the CO2 emissions are captured and stored. The most hype, however, revolves around green hydrogen which refers to hydrogen produced from renewable sources via electrolysis of water. Electricity is used to split water into its hydrogen and oxygen component parts.

Many countries are jumping on board the hydrogen train. Iceland, blessed with a wealth of renewable energy resources, has committed to becoming the world’s first hydrogen economy by 2050. In 2017, Japan launched its strategy to become a “hydrogen society”. Many other countries have their own hydrogen strategies including Australia, Korea, several European countries, Chile and Canada. These strategies involve significant government investments and subsidies.

The Hydrogen Council, a European industry lobby group, believes hydrogen could satisfy 18% of the world’s energy demand by 2050. We can probably take that as the optimistic view.

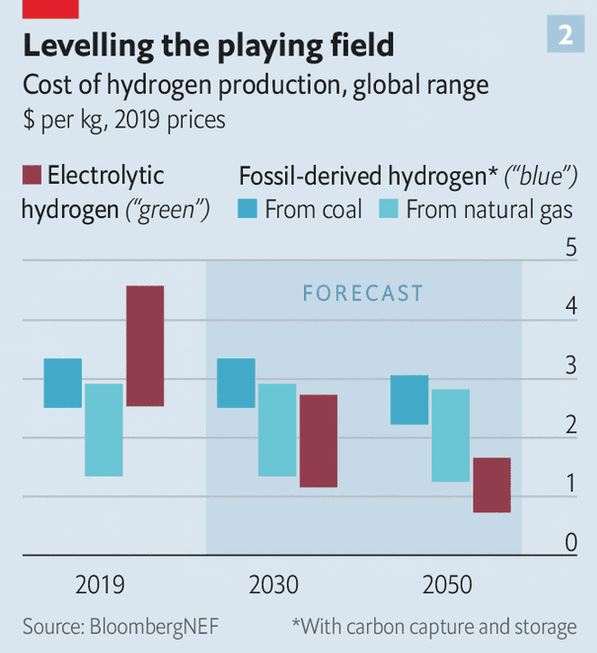

So will it happen? There are two main barriers. First, as usual, is the cost. At present gray hydrogen costs around US$1.50/kg, while green hydrogen is of the order of $2.50 to $5 per kilogram as shown in the accompanying graphic. It is hoped that technological improvements and scale production will dramatically reduce costs to under $1.50 over time, which, for comparison, is around two times the equivalent current cost of natural gas.

That’s the production cost side. Then there’s the challenges on the application side. Hydrogen for transport fuel will need to overcome the big head start of electric vehicles which deliver similar climate outcomes. Distribution and storage of hydrogen is another challenge, particularly if hydrogen is to replace natural gas for heating. Using hydrogen in steel making is being piloted but needs to be demonstrated at scale.

Hydrogen has been touted as a means of storing excess electricity generated by wind and solar sources. This can be attractive but the return-trip efficiency of using electricity to convert to hydrogen and then back to electricity is significantly lower than for battery storage or pumped hydro.

However, all of this skirts around the real issue: manufactured hydrogen is really electricity in disguise and its less efficient. This inbuilt inefficiency raises the question “why not simply power the end-use electrically, rather than using hydrogen as an intermediary?” There will be some applications in which hydrogen has obvious advantages, for example fuel to power shipping, replacing coke in steel making etc. In total, these applications will no doubt become a sizeable and growing sector of the economy. But ultimately, as much as I would like to see a flourishing hydrogen economy, I suspect that hydrogen will be like champagne – expensive but good for special occasions.

So, except for special circumstances like Iceland, beware of politicians who have a hydrogen strategy as the lead plank in their climate action strategy. It could become the successor to ‘carbon capture and storage’ – a technology that promised a lot but delivered little, and delayed real action on climate.

The writer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

Image Credit: akitada31 via Pixabay