In simpler times we used have community dances. Boys would congregate along one wall of the dance hall, and the girls on the other. Those brave enough would approach the other side and a dance would ensue, while the more timid stayed within the comfort of their respective groups. The same dynamic seems to be playing out in our energy transition. Climate skeptics think we are wasting vast sums on renewables, while the green lobby wants to stop all new fossil fuel production. There are very few willing to listen to both sides. But consider both sides we must because the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Erik Townsend is one of the few who has dared to cross the line and he lays out a compelling case for his energy transition proposal. Townsend has published his thoughts in a docuseries called Energy Transition Crisis which is available in both text and audio versions, and a video version is in production.

Let me try and summarize his premise:

Societal complexity, and therefore, the pace of advancement of humanity, is a function of the

amount of abundant and affordable energy available to the economy. This is the true underlying reason that humanity has made so much more progress in the last 200 years than it did in the 500 years before that. Whilst many people credit technology, it is actually a second-order effect, not the driving force.

Consider that one gallon of gasoline produces the same amount of useful work as up to 482 hours of human labor. When converted into dollar terms, gasoline energy is one thousand times cheaper than human labor.

Modern society is addicted to fossil fuels because we’re quite literally dependent on the

energy they provide for our survival and to feed ourselves. But if we continue to rely on fossil fuels for this energy, we’ll destroy the planet. We need a credible plan to replace fossil fuels with abundant clean energy we won’t run out of, and which won’t pollute our atmosphere with greenhouse gases.

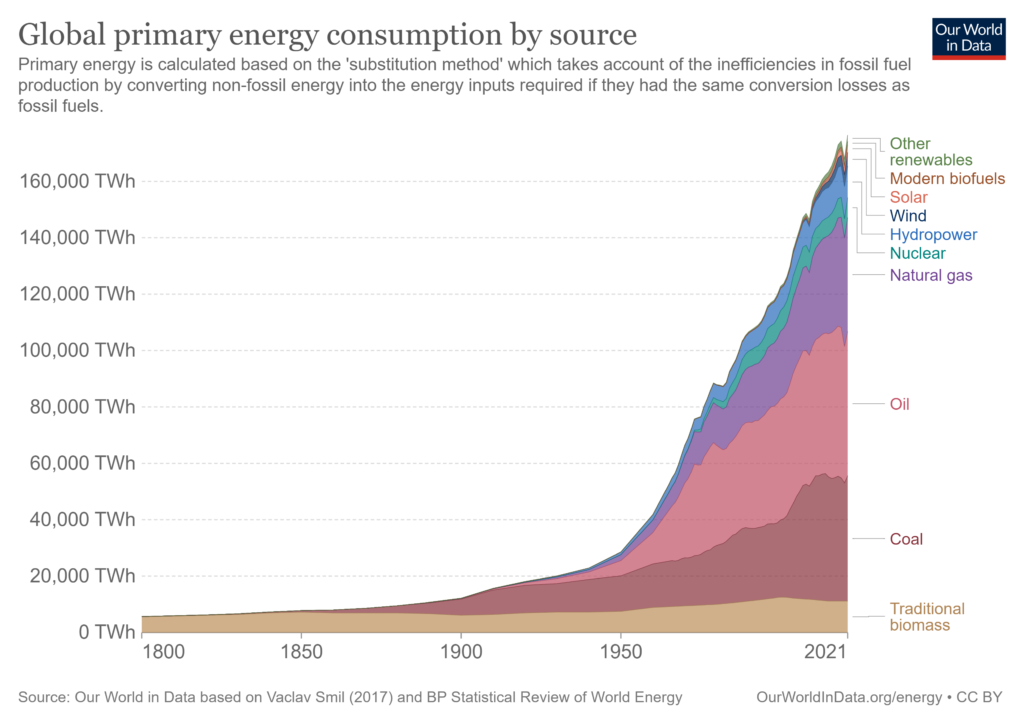

To illustrate the current situation, the accompanying chart shows global energy consumption broken down by source. At the end of 2021, more than 85% of our energy was supplied by the three primary fossil fuels.

Further, all the energy we get from every wind turbine and every solar farm ever built provides less than 2% of total energy consumption. The truth is we’ve only just barely begun this energy transition, even though it should have started in earnest decades ago.

Replacing fossil fuels is a much bigger undertaking than most people appreciate. Many people mistakenly believe that electricity or hydrogen are viable replacements for fossil fuels, and that the Electric Vehicle revolution already underway is going to solve our addiction to gasoline and diesel fuel.

But electricity and hydrogen are not sources of energy. Electricity is a wonderfully versatile way of transmitting energy from where it’s produced to where it’s needed, while clean hydrogen is a battery in disguise.

To electrify our world away from fossil fuels, several challenges exist.

We not only need to find enough new clean electricity to replace the energy we now produce by burning most of the coal (brown in the chart) and 40% of the natural gas (purple). We also need to replace almost all the oil (pink) with new clean electricity to charge all the vehicles that will no longer be burning liquid fuels.

Then there’s getting all that extra electricity from where it’s produced to where it’s needed. The current electrical grid in almost all countries is already running at or near capacity. Finally there’s the current state-of-the-art in electric vehicle batteries which depends heavily on lithium which is an environmentally challenging metal to mine. We’re also going to need lots of manganese, cobalt, graphite, and nickel. Not to mention the additional copper required. That’s a whole lot of mining that we don’t yet have in order to electrify the 95% of vehicles that still run on fossil fuels.

While these problems are solvable, they won’t be solved overnight. The number of years it will take to transition the global economy off fossil fuels, even if we make it our top priority, will be greater than the number of years we have left before cheap oil peaks and starts to drive energy prices to economy-damaging levels. Like it or not, we depend on energy from oil for almost everything we do.

But because of environmental concerns, extractive industries such as mining and oil & gas exploration and production, have been off limits for many institutional investors. The result is a lack of the investment that’s needed just to maintain current levels of oil and gas production and maintain the momentum of supply of electrification metals.

To make matters worse, an analysis of the rate of implementing wind and solar projects demonstrates that even if we build more wind and solar at twice the annual pace we have been, assuming we can meet the metals demand, it would still take two more decades before we could even begin phasing out fossil fuels. And even if we further double this assumed rate of growth, we still don’t get to replace all fossil fuel use by 2050.

And this creates the dilemma that people are reluctant to talk about.

Depletion of existing oil producing resources, lack of investment to replace them, and exhaustion of spare production capacity, are all coming together to form a perfect storm on the near horizon for the global crude oil market. A global energy crisis will be the unavoidable result.

When oil prices inflate, it’s not just a matter of pushing a button to make more supply. It takes a long period of high energy prices to incentivize new investment in a hostile regulatory environment, and the economy will feel that pain for a period of years until more supply can be brought online.

In order to make real progressin this energy transition, we need to continue building as much wind and solar capacity as possible, but we also need a credible plan to keep fossil fuel costs at affordable levels while we supplement wind and solar with viable alternatives that can scale up to meet our base load electricity needs.

So Townsend’s conclusion is that we need to do the following:

- Conserve energy with aggressive energy and thermal efficiency programs

- Aggressively build out wind and solar energy resources

- Invest in oil and gas sufficient to ensure that we don’t encounter an energy crisis during the decades-long transition, and increase mining of battery metals to meet burgeoning demand

- Rapidly implement clean base load power generation

- Research better ways to produce synthetic liquid fuels

The third dot point, “investing in oil and gas”, is anathema to climate action advocates. Their case is that it is just a pretext for continuing production of fossil fuels. However, if you accept that an energy crunch is coming, there will be two sides blaming each other. The fossil fuel industry will blame the lack of investment caused by restrictive policies, while the greens will blame politicians for not investing enough in renewables. They both have a case.

The fourth dot point, “implement clean base load power”, is easier said than done. Townsend’s solution is two-fold.

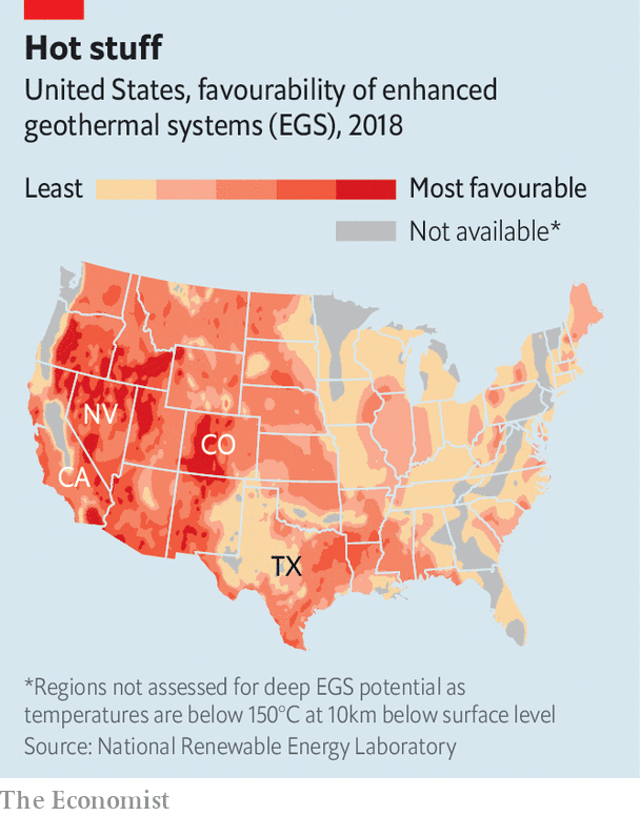

First, invest heavily in technology to develop geothermal energy from hot rocks underground which is practically a limitless source of energy. However the technology doesn’t exist to allow large scale drilling to the depths and temperatures required to extract this energy. Nevertheless, the potential is huge. The map shows the most prospective sites in the USA. The recent Inflation Reduction Act of the Biden administration provides incentives for geothermal development and there are a number of promising demonstration projects in progress.

The second part proposed by Townsend is the use of small modular nuclear reactors using thorium-based molten salt technology. There are obvious public acceptance issues with this proposal. Nevertheless, I recommend reading Townsend’s description of the historical development of this reactor, and in particular how light-water technology won out over the safer molten-salt technology in another classic VHS vs Betamax story.

A problem that Townsend fails to address with either of these solutions is that they equally suffer from the lack of ability to build out at sufficient scale in the requisite time. Indeed, the Department of Energy hopes that geothermal energy will account for 8.5% of total American electricity generation by 2050.

But this doesn’t detract from the key message here. We face a horrible dilemma. Despite our best efforts, fossils fuels are going to be around for quite a lot longer than what we would like. How do we balance energy availability and reliability, public affordability and climate?

Although my first reaction would be that climate must take priority, I am conscious of the sudden reduction in climate action after the GFC when short-term concerns took priority. We can ill afford a repeat at an even bigger scale due to an energy crisis, and we saw a glimpse of that after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

I don’t have an answer but just as in the dance hall, I suggest all ‘sides’ move from the comfort of their groups to the middle, so that we can engage with each other to determine the best way forward in the energy dance. Kudos to Erik Townsend and others like Art Berman for starting the conversation.

The writer is a co-author of Court of the Grandchildren, a novel set in 2050s America.

Image by Gerd Altman from Pixabay